Richard.

Posted: October 29, 2008 Filed under: Alzheimer's 1 CommentRichard, who has Alzheimer’s, lived for a while next door to us with his daughter. His advancing disease made it necessary for his safety to move him to a Sunrise facility, where he seems to be doing very well. We visited him for the first time there a few days ago.

One thing about our call on Richard was especially poignant to me. We visited for a while in his room (a bright space, attractively furnished), and on the dresser was one of those double-frames for photos with, on the left, a picture of Richard as a young man in the early 1940s, and, on the right, a picture of his wife (now long deceased) from the same time. From our conversation, we knew that Richard still knows that the young man and woman in the pictures are he and his beloved. We sat and talked some more, and Richard put on a CD. Richard loves Sinatra, and so do I, so it was no surprise to me that the disc he played was of the young Frank with the Tommy Dorsey band. I commented, “Ahh, Sinatra” — at which point Richard went over to the dresser, and, pointing alternately to the CD player and the photograph of himself, protested, “That’s me.” It was obvious he had conflated his own identity with the sound of Sinatra’s voice in that period. Then a girl singer took over the vocals on the track we were hearing, and I recognized her as Connie Haines. So I said so, and Richard again disagreed strongly, going back to the double-frame and pointing to his young bride, saying, “That’s her.”

Somehow, he was able to hold two ideas in his head at the same time. He knew the photographs were of him and his wife. But he also “knew,” just as certainly, that the photographs were of the singers on the CD, the singers making the music that meant so much to him. The music which began as a metaphor for himself and his wife when they were young had gone beyond metaphor; now the two of them had become the music, and the music had become them.

When we read a work of fiction, the story can draw us into its world; while we read, we are not here, we are “there,” we become the protagonist in our mind’s eye; his fears are ours, his triumphs are ours. The difference is while this is so, we never quite lose the part of ourselves that says, “I am me, reading this book.” Richard, when he hears the music, seems to lose that.

Maybe it’s because music means a lot to me, too, or maybe it’s because the music of his time meant a lot to my father, whom we lost to Alzheimer’s, but when I realized what was going on with Richard, I started to cry, then held back my tears. At the same time Richard’s confusion is a symptom of his disease, there’s something beautiful in it. Counterintuitively, the disease doesn’t always cloud truth — sometimes it reveals it. And the truth can be a beautiful thing.

Found in the Shuffle.

Posted: October 24, 2007 Filed under: Alzheimer's 8 CommentsDon’t tell me the “shuffle play” on my iPod doesn’t know what it’s doing.

My father died from Alzheimer’s last February after a ten-year decline. Two weeks ago I was about to fly back home, as I have been doing about once a month since his death, to look after my Mom. I knew she and I would be visiting his grave. Not a day goes by that my father isn’t with me, but naturally, on the eve of this visit he was even more keenly at the center of my consciousness.

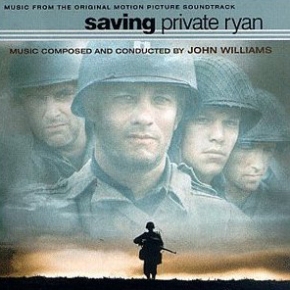

My iPod has over 4000 songs on it. Two of these tracks are different versions of the same piece of music: John Williams’ “Hymn to the Fallen,” his theme for the present-tense scene at the end of Saving Private Ryan in which the now-old Ryan visits the graves of his comrades. One version on my iPod is from the original soundtrack; the other is a re-recording by the City of Prague Philharmonic.

the other is a re-recording by the City of Prague Philharmonic.

I love this piece, partly because it is gorgeous music, but also because it has associations with my father for me. On a surface level the music honors his World War 2 service just as it does the movie’s characters’. But the deep level on which the music communicates to me has to do with my father’s long fight with Alzheimer’s. I conceived my father as engaged in a war with it, one it was winning and would win for good. At some point, although my father was alive and would remain so for years, my real father, the one inside, became one of “the fallen” that “Hymn to the Fallen” now memorialized for me. The piece–stoical, unsentimental, brave, noble, ineffably sad–was my father’s tragedy in music; it continued to be that, for me, for the rest of his years; and it is that now.

Music can do important things for us. This piece, somehow, helped me make sense of something that seemed to make no sense. Gave meaning, some kind of beginning middle and end coherence, to a story the end of which lacked coherence. Connected me to my father in a way I needed to be connected, when connection through any other means was no longer possible.

Back to the day that preceded my most recent trip back home. I was at the gym, on the elliptical. My iPod’s shuffle-mode decided to play the original soundtrack version of “Hymn to the Fallen.” What are the chances of that? Of having that piece come up, out of 4000-some possibilities, on the eve of my trip, when my father, his Alzheimer’s, the upcoming trip to his grave, were so present in my mind? Ah, you say, coincidences happen. But wait till you hear this. As soon as that track finished, the very next selection that played, out of the other 4000-some possibilities my iPod could have picked, was the other rendition of “Hymn to the Fallen,” from the City of Prague Philharmonic.

(If you wish to hear a short excerpt from the six-minute soundtrack version, you can do so by clicking here.)

Apple has kept it very hush hush, but it’s obvious enough—our iPods know us. When you select shuffle play, what you’re really doing is telling your iPod to play the music it knows you need to hear.

Hero.

Posted: May 25, 2007 Filed under: Alzheimer's 3 CommentsWhen I saved several pieces of ledger and legal-pad paper containing my father’s jottings a few years ago, I had never heard of the word “blog.” But last week, when I came upon them for the first time since then, I decided I should write about them.

My father’s responsibility to his wife and children caused him always to keep a close eye on the family finances. (I think he defined himself by his sense of responsibility.) So when, in his “golden years,” statements from his financial institution started arriving that didn’t make sense to him, he was driven to figure out why. He never could. What he didn’t realize was that there was a reason he never could. The Alzheimer’s that had taken away his ability to add and subtract had also taken away his ability to know that he was unable to add and subtract. So month after month he kept trying. On my visits, he would show me his cipherings, numbers that “proved” to him that money had mysteriously gone missing from his and my mother’s accounts.

his ability to add and subtract had also taken away his ability to know that he was unable to add and subtract. So month after month he kept trying. On my visits, he would show me his cipherings, numbers that “proved” to him that money had mysteriously gone missing from his and my mother’s accounts.

Of course, you can’t double-check a statement when you can’t do arithmetic anymore. In some cases it’s not even clear that the characters he wrote down were numbers, or letters; some of them seem to be hybrids of the two, or just shapes and squiggles, hieroglyphics. He would put one line under the other, and come up with a sum or a difference, but one devoid of meaning.

I knew it wouldn’t allay his anxiety if I just said, “Dad, they wouldn’t make an error of that kind.” My mother had tried that. I needed to be able to tell him, and mean it, “They didn’t make an error of that kind.” And the only way to do that was to go through all his statements for the previous twelve months and reconcile them myself. It didn’t matter that I was certain of the answer I’d find; I knew that settling his fears would require not pretending to take him seriously, but taking him seriously. Luckily, when he saw that where I came out was based on computation and not an assumption of what “had” to be so, it would make him feel better.

I didn’t really know at the time why I wanted to save all those pages of his, but now I do. They represent to me my father’s valiant, impossible effort to go on being himself, his responsible, diligent self, even long after disease had robbed him of any shred of ability to do that. I think there’s heroism in that. These pages make me feel sad, but they also make me feel proud.

diligent self, even long after disease had robbed him of any shred of ability to do that. I think there’s heroism in that. These pages make me feel sad, but they also make me feel proud.