The Voice of Christmas: Karen Carpenter

Posted: December 18, 2010 Filed under: The Great American Songbook 3 CommentsKaren Carpenter was the Great American Songbook singer who wasn’t. On most Carpenters albums, her material, with some exceptions – I Can Dream, Can’t I?; When I Fall in Love; Little Girl Blue – while superior, was of the 1970s and not the Golden Age. There is, however, an album containing many examples of Karen Carpenter assaying the Great American Songbook; it is the Christmas LP the Carpenters released on A&M in 1978, Christmas Portrait.

That record, along with the follow-up An Old Fashioned Christmas issued a year after Karen Carpenter’s 1983 death, are contained on the 2-CD set Christmas Collection. They prove her death was more than privately tragic. She had the talent, the affinity for the material, and the wide contemporary appeal to have kept the Great American Songbook flame burning into our present time and beyond. But we do have this.

Richard Carpenter here surrounds his sister with orchestral and choral-group arrangements comparable to those one might hear in the glory days of MGM musicals, when Conrad Salinger, Hugh Martin and Kay Thompson worked in that studio’s music department. The material demonstrates how Christmas brought out the best in our songwriters. Fourteen songs on this set are Great American Songbook entries, several of them uncommon (e.g. The First Snowfall, by Sonny Burke and Paul Francis Webster, Sleep Well Little Children, by Leon Klatzkin and Alan Bergman, and It’s Christmas Time by Victor Young and Al Stillman). Various instrumental medleys feature Richard at the piano. As for the vocals, the spotlight is Karen’s. With her dark, melancholy alto, the way she subtly scoops up to her notes, the texture in her voice as it ever-so-softly cracks, and her empathic understanding of lyrics, she fashions a style that feels less like a style than the sound of a human heart breaking.

Take I’ll Be Home for Christmas. The song is a story with a killer twist of a last line, one that reveals the singer’s promises of returning home for Christmas are lies, mere fantasy – that the only way the singer is going anywhere, alas, is in her dreams. The pain in that line is nowhere to be found in most renditions. When Karen sings “if only in my dreams,” the pain is more than palpable, it’s exquisite.

If it’s a truism that only one who knows despair can know joy, Karen proves it on the happier material. You can feel the winter air on her Sleigh Ride, you can breathe in the roasting chestnuts in her Christmas Song. She takes songs you thought you never needed to hear again and makes you hear the greatness in them.

An example of the care lavished on this work is that Carpenter sings the little known verses to the songs. Let me spit it out: This is the best Christmas album ever made. For those who have it, it wouldn’t be Christmas without it.

By the way, the album owes a debt to an earlier one, by Spike Jones. It was called Xmas Spectacular, and came out on Verve in 1956. It’s an album in which Jones strayed from his comedic style to play the material (mostly) straight, and it had a large influence on Richard and Karen Carpenter. In the CD reissue of the Jones album (titled Let’s Sing a Song of Christmas), Richard Carpenter had this to say in the liner notes:

In December 1956, my father I visited The Music Corner, one of several record shops in my hometown of New Haven, Connecticut. To my delight he purchased Spike Jones’s newly released Verve LP Xmas Spectacular. Upon my first hearing, the realization came to us that the album was ‘straight,’ with only a modicum of glugs and whistles employed.

…The album was played innumerable times every Christmas in our home and had quite an impact on Karen and me. When we recorded our Christmas Portrait album (1978) I patterned it after the Jones LP, not only in the use of certain medleys, but also including some of the melodic but lesser known titles Spike had used, such as ‘It’s Christmas Time’ and ‘The First Snowfall.’ Xmas Spectacular is a timeless album; our children faithfully play it every Christmas season. I am delighted to see it released yet again and honored to have been asked to write these notes.

It may be a little late for you to pick up these albums in time for Christmas, but if you can, do. And if you can’t, pick them up for next Christmas.

Carole King, James Taylor, and The Great American Songbook.

Posted: May 25, 2010 Filed under: Reasons to Live, The Great American Songbook, The Great Songwriters 3 CommentsLena Horne Crosses the River.

Posted: May 19, 2010 Filed under: Reasons to Live, The Great American Songbook 1 CommentWatch and listen to this rendition of Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Moon River,” from a Bell Telephone Hour broadcast of 1965. It’s similar to, but somewhat slower than, the version Lena recorded around the same time for United Artists Records.

When I hear this performance, I hear something I’ve never picked up in any other singer’s version — something hiding in plain sight in the song all along, because it’s in the very first line. “Wider than a mile, I’m crossing you in style some day.” When Lena sings these words so introspectively and yearningly, yet proudly, I hear her memory of a young black woman looking across an expanse separating her from a white world of freedom, equality and privilege, and wanting to be a part of it, determined to be a part of it, someday.

All the thousands of times I’ve heard the Mercer lyric before, I’ve thought of the river only in terms of flow, of movement with the current, along the river’s lengthwise dimension. (For that is where most of the song lives: “two drifters off to see the world.”) But that very first line, the one that’s always been there but which it took Lena’s version to make me hear, describes an action perpendicular to flow — crossing the river. And doing it by an act of will. Not transcending the divide as if it weren’t there, but consciously crossing it, getting to the other side of it, where the good things in life are; and doing it with dignity intact despite the formidable problem that it is “wider than a mile.” (Doing it “in style.”) No other singer brings that out, even though by Mercer’s putting it right up front you’d have thought he made it impossible to miss.

I don’t know if the divide Mercer had somewhere in the back of his mind, when he imagined meanings the song might have, was a racial one. But I do know now, as I never did before hearing Lena’s TV version, that Mercer is yearning for something he doesn’t have on that opposite river bank. If Lena used her own history to find a meaning in that divide, then she did what all singers should do — bringing her full humanity to the song, and by so doing, illuminating it.

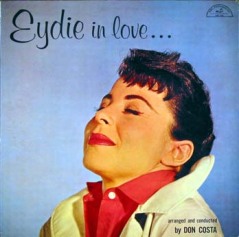

Harvey Pekar Digs Eydie Gorme.

Posted: October 22, 2009 Filed under: Harvey Pekar, The Great American Songbook 3 Comments

When comic book writer Harvey Pekar stayed with us for a few days over the summer, we listened to some CDs together, and I decided to lay on him some of my favorite discs by Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme. This was a risk. Steve and Eydie are widely understood (by those who misunderstand them) to be far from hip, while Harvey’s hipster credentials are impeccable — DownBeat record reviewer in the 1960s, advocate for jazz’s avant-garde in numerous articles and reviews,  author of a libretto for a jazz avant-garde opera (Leave Me Alone, premiered at Oberlin College earlier this year) the subject of which was the avant-garde itself. So I was delighted to discover that Harvey is an Eydie Gorme fan, with an appreciation for Lawrence as well.

author of a libretto for a jazz avant-garde opera (Leave Me Alone, premiered at Oberlin College earlier this year) the subject of which was the avant-garde itself. So I was delighted to discover that Harvey is an Eydie Gorme fan, with an appreciation for Lawrence as well.

“She’s got great time, man…Her breath control is really amazing…I’ve always liked her.” I’m paraphrasing a bit, because it’s been about four months since our listening session, but that was the gist of it.

This gratified me immensely. It’s hard to make a case that someone as well-known as Eydie Gorme can be called underrated — it makes no sense, on the face of it — but I think the word applies, because, famous and successful as she is, her name seldom comes up when people make their lists of the great female singers of the American Songbook. Other deserving names always come up: Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee, Sarah Vaughan, Barbra Streisand. Never Eydie Gorme. But listen to the body of work which Eydie recorded alone or with Lawrence in the fifties through seventies, and you hear a singer of astonishing gifts. Her intonation, range and control are second to none. She swings.  She has humor. Her interpretations can be warm-and-gentle, or broad-and-brassy. (She’s more often remembered for the latter style, since she made something of a shtick of it in the sixties, but there’s plenty of recorded evidence of her lovelier and more restrained singing as well as singing from her that is pure, exhilarating excitement.)

She has humor. Her interpretations can be warm-and-gentle, or broad-and-brassy. (She’s more often remembered for the latter style, since she made something of a shtick of it in the sixties, but there’s plenty of recorded evidence of her lovelier and more restrained singing as well as singing from her that is pure, exhilarating excitement.)

To some extent Steve and Eydie brought their undervalued status upon themselves, by making self-parody and self-deprecation (and deprecation of each other) a part of their act — they actually seem to relish their Vegassy reputation, which does them a partial disservice — but their recorded legacy on ABC-Paramount, United Artists, Columbia and RCA in the fifties, sixties and seventies stands as testament to their true artistic contribution to classic pop. Their singing in those years, together and apart, with the arrangements of giants like Don Costa, Marion Evans and Pat Williams, was simply superb. If Ella and Peggy were jazz, and Sinatra was jazz-pop, Steve and Eydie are pop  inflected by jazz with several teaspoons of musical-comedy theatricality thrown in. Which makes their recipe uniquely treasurable. I do feel slightly defensive about my appreciation of them sometimes, because it’s not the most popular opinion or the conventional wisdom even among fanciers of The Great American Songbook — so discovering that I have company in Harvey Pekar made me feel pretty good. I always knew they were hip.

inflected by jazz with several teaspoons of musical-comedy theatricality thrown in. Which makes their recipe uniquely treasurable. I do feel slightly defensive about my appreciation of them sometimes, because it’s not the most popular opinion or the conventional wisdom even among fanciers of The Great American Songbook — so discovering that I have company in Harvey Pekar made me feel pretty good. I always knew they were hip.

The Book on Johnny Mercer.

Posted: June 16, 2009 Filed under: The Great American Songbook 8 CommentsThe biography of lyricist Johnny Mercer by Philip Furia was recenty recommended on the Songbirds list by eminent jazz critic/historian Dan Morgenstern, and that recommendation alone necessitated my reading it.

My take: I can see why Dan liked the book, while I found some things about it ridiculous or aggravating.

First, the good news. Much of the book’s value is due to Furia’s having had access to an unpublished autobiography by Mercer, which resides with the Johnny Mercer Papers at Georgia State. I never knew the Savannah-born lyricist, supreme commander of the American vernacular — collaborator with Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen, Harry Warren, Richard Whiting, Arthur Schwartz, Hoagy Carmichael, Henry Mancini and many other composers (Mercer would write with anyone he respected, becoming the most promiscuous of the great lyricists) — had written the story of his own life. This is colossal news, and reason enough for the Furia book’s existence. I would love to see Mercer’s tome published someday, even if it is in an unfinished state. It may be the new Holy Grail for us who are into that sort of thing. In the meantime, Furia relies on it heavily and quotes liberally from it, which will do.

He relies as well on interviews and articles contained in the Johnny Mercer Papers, and on an archival interview with Mercer housed at Georgia State. And, in the later chapters covering the fifties, sixties, and seventies, decades that yield people still living who knew the pantheon-level lyricist, Furia has collected good material from his own interviews.

Georgia State. And, in the later chapters covering the fifties, sixties, and seventies, decades that yield people still living who knew the pantheon-level lyricist, Furia has collected good material from his own interviews.

But the book suffers a flaw. It has a “thesis.” And Furia, like a caricature of a university academic (he is, in fact, a real one), won’t let go of it: Mercer’s life and work post-1940 were completely shaped by his affair with Judy Garland.

Over and over we read that this or that deeply-felt Mercer lyric owed its existence to his lifelong frustrated love for Garland. That when Mercer wrote (X) in song (Y), he was writing “about” this love. Furia wants us to believe Mercer’s love for Garland informed every yearning lyric he ever wrote and every melancholic bender he ever went on.

It’s reductionist hogwash. Let’s stipulate that Mercer did have an affair with Garland and that he never got over it. (I don’t know that this is so, but let’s stipulate it.) Is there no other way to understand the life and work of Johnny Mercer than through this prism? Could any of Mercer’s love lyrics have been about, say, another woman that he had feelings for along the way, or a yearning for something else entirely? Could any of Mercer’s lyrics rise to the level of poetry, such that they transcend simple decoding? Not according to Furia, who insists on making the Garland affair Mercer’s Rosebud. You sense that Furia feels he has made a major discovery, and his unwillingness to let you forget his triumph is palpable. Over and over he forces everything through his funnel, to a point of such ludicrousness that the reader would laugh if it weren’t such a sin to have an otherwise worthy book marred this way.

Furia also cares inordinately about when Mercer and his wife-to-be Ginger first had “sexual intercourse,” as he puts it. I don’t know why, but he insists on reading Mercer’s letters to Ginger with the help of some sort of “sexual intercourse” Ovaltine decoder ring, as if determining the moment Mercer lost his virginity (and yes, Furia has a point to prove about this) matters. Furia teases out the meaning of every word in these letters, barely containing his excitement that he has discovered the occasion of Mercer’s deflowering. Suffice it to say he is unconvincing. The passages that Furia cites can be read in other ways, to mean other things. But let an academic latch onto a thesis and he’s like a dog with a bone…

At any rate, the book is more than worth reading, infuriating flaws and all (hey, I just realized Furia is infuriating’s middle name), and is available from many book dealers in new and used form, both hardcover and paperback, at a wide range of prices including the eminently reasonable and downright cheap, here and here and here.

Cover Versions.

Posted: May 11, 2008 Filed under: The Great American Songbook | Tags: Album Covers, Basie, Great American Songbook, Sinatra Leave a comment

Speaking of Sinatra-Basie (and I just was), here are shots of the original LP front and back cover.

These are from John Brown’s website Sinatra Album Covers, a treasure trove of high-res, larger-than-life (meaning, larger than CD—you know, like records used to be) scans. Fun to browse through.

Edited much later to add: The Sinatra Album Covers website no longer exists.

Check, Please.

Posted: May 6, 2008 Filed under: The Great American Songbook Leave a commentOne form of autograph collecting is the acquisition of cancelled checks, which somehow make their way into the hands of collectables-dealers. For those who, like me, are interested in collectables to do with the Great American Songbook, here are two bank checks written by titans of the art. They were purchased on eBay by my wife as a gift for me.

The first was written by lyricist Sammy Cahn on the joint account he shared with his wife Tita, on July 1, 1972.  It is written to Cafe “72” in the amount of $30.00 and contains, on the memo line, the words “Book Pub.” Perhaps this dinner was connected to the enjoyable autobiography he was to publish in 1974, I Should Care: The Sammy Cahn Story . A stamp on the back of the check indicates that Cafe “72”was a New York establishment, but a quick Googling doesn’t produce any businesses by that name still in existence there. I like the size of Cahn’s signature on the check. Cahn (at least in his public persona) was not known for excessive modesty–nor should he have suffered from this, given his resumé. (Four Oscar wins, thirty nominations, Frank Sinatra’s “house lyricist” in the fifties and sixties, etc.) The signature is congruent with the persona.

It is written to Cafe “72” in the amount of $30.00 and contains, on the memo line, the words “Book Pub.” Perhaps this dinner was connected to the enjoyable autobiography he was to publish in 1974, I Should Care: The Sammy Cahn Story . A stamp on the back of the check indicates that Cafe “72”was a New York establishment, but a quick Googling doesn’t produce any businesses by that name still in existence there. I like the size of Cahn’s signature on the check. Cahn (at least in his public persona) was not known for excessive modesty–nor should he have suffered from this, given his resumé. (Four Oscar wins, thirty nominations, Frank Sinatra’s “house lyricist” in the fifties and sixties, etc.) The signature is congruent with the persona.

The second is a check written by singer Mel Torme on the Mel Torme Productions, Inc. account, for $64.15, to the Curious Book Shop in Los Gatos, CA on September 5, 1989.  Torme was known to be an avid reader. As recently as 1998, the Curious Book Shop was listed as one of the three best places for used books in the Santa Clara Valley, but it exists no longer.

Torme was known to be an avid reader. As recently as 1998, the Curious Book Shop was listed as one of the three best places for used books in the Santa Clara Valley, but it exists no longer.

Great “American Song” Book: The House That George Built.

Posted: November 8, 2007 Filed under: The Great American Songbook Leave a commentIn novelist and essayist Wilfrid Sheed’s latest book, each chapter is essentially a monograph on the life and work of one or  another of the creators of the Great American Songbook. (That body of song written mostly for Broadway and Hollywood and mostly from the 1920s through 1960s, extending out a bit on either end.) Together the chapters cover most of the usual (and wonderful) suspects: George Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Arthur Schwartz, Jimmy Van Heusen, Johnny Mercer, et. al. The book is an impressionistic study, but impressions can be valuable when they come from someone with something to say.

another of the creators of the Great American Songbook. (That body of song written mostly for Broadway and Hollywood and mostly from the 1920s through 1960s, extending out a bit on either end.) Together the chapters cover most of the usual (and wonderful) suspects: George Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Arthur Schwartz, Jimmy Van Heusen, Johnny Mercer, et. al. The book is an impressionistic study, but impressions can be valuable when they come from someone with something to say.

Three streams meet to provide the book’s source material. The first is Sheed’s reading of all the previous biographies. The second is observations that the songwriters (while they still lived) shared with Sheed in private conversation, about themselves and each other. The third is Sheed’s intimate familiarity with, passion for, and lifelong study of the music.

You might think the first stream has limited value–do we really need a digest of what’s already been written?–but the value is in Sheed’s critical eye and his powers of synthesis. He proves an astute “culler” of the available material, sorting the wheat from the chaff adroitly, and he puts the good bits together to build a persuasive narrative of the interior lives of these composers and lyricists. Some of his extrapolations from the available material are based on intuition, conjecture and speculation–and he is not shy about admitting this when it is so–but it’s informed speculation, and a master novelist’s superior insight into motivation, that he brings to the party. And so the results are seldom less than convincing, and never unworthy of consideration.

You might think the first stream has limited value–do we really need a digest of what’s already been written?–but the value is in Sheed’s critical eye and his powers of synthesis. He proves an astute “culler” of the available material, sorting the wheat from the chaff adroitly, and he puts the good bits together to build a persuasive narrative of the interior lives of these composers and lyricists. Some of his extrapolations from the available material are based on intuition, conjecture and speculation–and he is not shy about admitting this when it is so–but it’s informed speculation, and a master novelist’s superior insight into motivation, that he brings to the party. And so the results are seldom less than convincing, and never unworthy of consideration.

As for the second stream, during his sixty-plus years in this country Sheed (English by birth) made the acquaintance of several of the great GAS songwriters and those who knew them. (Sheed came here as a lad in 1940 and immediately fell in love with the music.) What they shared with Sheed, even if in some cases in only one or a few conversations, went beyond mere anecdote to include their perceptions of themselves and one another. And, of course, Sheed was able to form his own impressions of these writers from his encounters with them. A significant amount of this material is fresh, and hence, invaluable. Sheed integrates this data into his life/art narratives, the stories he builds about his subjects and their distinct contributions.

beyond mere anecdote to include their perceptions of themselves and one another. And, of course, Sheed was able to form his own impressions of these writers from his encounters with them. A significant amount of this material is fresh, and hence, invaluable. Sheed integrates this data into his life/art narratives, the stories he builds about his subjects and their distinct contributions.

Although yet another quality Sheed brings to the book is a keen ear for the music, I didn’t always agree with him, and there are inaccuracies and errors. But these are minor complaints in light of the book’s qualities. And Sheed’s writing (last but definitely not least) is a joy to read. His prose is almost too rich here, causing you to rinse, lather and repeat just to appreciate all the nuances and felicities of language and allusion, but it’s too much of a good thing, not too much of a bad thing. The book, when all’s said and done, is fun. Sheed doesn’t strain for wit, he’s just born that way.

A Glimpse of the Eternal: Steve and Eydie.

Posted: November 5, 2007 Filed under: Phenoms, The Great American Songbook 1 CommentWhen the Steve and Eydie show at the Paramount Theatre in Aurora (about 40 miles west of Chicago) was announced, I resisted. I said, “We saw them in 1997–how different is their act going to be now?” And, “Ten more years have passed. Time will surely have taken its toll on them.” And, last but not least, “It’s Aurora. Who wants to go to Aurora?!?”

But about two weeks ago, another voice piped in. It said, “You idiot. If you don’t see them now, you may be forfeiting your chance to see them ever again. None of us is guaranteed to be on the planet tomorrow, let alone a year or two from now. You might be gone, either of them might be gone…The only thing we know is you’re here, and they’re here.”

So I carpied the diem, and scored a good seat. I’m glad.

The show opened with a montage of TV clips of S&E separately and together from the 50s through the 70s. You came away awed at the contribution they made to the mainstream culture all those years, making popular music popular at impossible-t0-take-for granted-now levels of artistry. Not to get cosmic about it, but the montage made me deeply grateful that so much of my time on the planet has coincided with so much of theirs.

The show opened with a montage of TV clips of S&E separately and together from the 50s through the 70s. You came away awed at the contribution they made to the mainstream culture all those years, making popular music popular at impossible-t0-take-for granted-now levels of artistry. Not to get cosmic about it, but the montage made me deeply grateful that so much of my time on the planet has coincided with so much of theirs.

At the close of the montage, Steve and Eydie came out on stage and sang a snappy piece of special material called, I’m thinking based on the lyric, “We’re Still Here” (not based on Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here”). The very first line of the song was funny. Making reference to the video just seen on the big screen, they sang, “We don’t look like that anymore.”

It was a shrewd lyric line to open with, because it disarmed an issue that had to be dealt with. Eydie doesn’t look like that anymore. She’s a bit rounder. She still looks great, and, my God, at 76, and with her recent knee surgery, if she’s rounder, she’s entitled. But she’s looks great in a different way than you might be expecting. Steve, thanks to the miracles of modern science and/or clean living and/or genetic luck, looks pretty much the same as always!

“We’re Still Here” turned out, as it went on, to stimulate cosmic thoughts similar to those I had while watching the montage. The song wasn’t just about that they were still here. It was about that all of us, we the audience as well as they, were still here. It was a celebration of survival. Not in the Sondheimian sense of having made it through Herbert and J. Edgar Hoover; rather in the sense that every day you wake up not dead yet is a gift. By virtue of the fact that they were on the stage, and we were in the audience, not one person there was dead yet! And that is something to thank the universe for. It was the unspoken theme of the entire show. Not to exaggerate, but the show was a religious experience.

And the show was a celebration of the survival of pop music excellence. It is just hanging on by a thread in this world, breathing its last breaths, but it is still here, for just a little while longer anyway. It is not dead yet. And this spirit, as beautiful as it is tragic (for we know what the future has in store), informed the entire show. When Steve and Eydie duet on Rodgers and Hart’s “Where or When” (a staple for them for many years), the song is no longer about a couple who meets for the first time with a sense of deja vu–it’s about all of us who love the Great American Songbook, performers and audience, meeting over and over again to share it with each other. And it takes on new qualities of the eternal, as we allow ourselves to imagine doing so in the next world when this one is through for us.

vu–it’s about all of us who love the Great American Songbook, performers and audience, meeting over and over again to share it with each other. And it takes on new qualities of the eternal, as we allow ourselves to imagine doing so in the next world when this one is through for us.

As an experiment, I closed my eyes at times and tried to imagine a young Steve and Eydie on stage, to determine if the sounds I was hearing would make sense with that picture. My rough guess is that the answer was yes about 75% of the time–which I think is amazing, and (getting all spiritual again) inspiring. The other 25% of the time there were signs of wear. But their musical instincts are sharp and they were able to “work around it” much of the time. When Eydie sang some of her hits, she employed some sensible melodic inversions in order to stay out of difficult territory. Yet at times she went for the high notes–and nailed them.

In their patter, Steve and Eydie didn’t miss too many chances to plug their website–steveandeydie.com–and neither will I. If you click on those words in this post, you’ll be taken right there. You’ll find many of their albums, separately and together, remastered for CD. I particularly commend to you the twofer composed of Two on the Aisle and Together on Broadway. The music of  Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme exists at some kind of nexus of jazz and Broadway anyway, so the program of these two albums, tunes from Broadway shows of the midfifties through midsixties arranged by Don Costa and Pat Williams, is right in their wheelhouse, and they knock it out of the park.

Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme exists at some kind of nexus of jazz and Broadway anyway, so the program of these two albums, tunes from Broadway shows of the midfifties through midsixties arranged by Don Costa and Pat Williams, is right in their wheelhouse, and they knock it out of the park.

Why post about Steve and Eydie now? Who doesn’t know about them, or, at least, of them? Well, while it’s important and exciting to talk about Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition (as Down Beat used to put it), it’s also a good thing now and then, for the sake of perspective, to reaffirm the Talent That Once Received So Much Recognition That It Now Receives None At All. To reaffirm, for the record, the phenomenality of phenomenons.

After the show, in the garage where I had parked a couple blocks from the theater, I shared an elevator with one of the musicians, a guy in his early forties. I complimented him on the show, and he said thanks. He said, “So what did you think of them?” I said, looking him straight in the eyes, “I think it’s a miracle.” He looked back at me and paused, struggling for something to say, and then replied, nodding, with awe in his voice. “I think that’s right. I think that’s the only word for it.”

Nat, Ella, Peggy, Jo, Sarah, Mildred, Frank, Tony, Jackie, June, Rosemary, Bing, Vic, Sammy, Doris, Audrey, Lena, Chris, Carol, Mel, Barbra, Barbara, Keely, Daryl, Bobby, Mabel, and Other Delights.

Posted: June 21, 2007 Filed under: The Great American Songbook 1 CommentBack at the turn of the century, a “cyber-zine” once lived, under the leadership of David Torresen. Called Songbirds, and dedicated to the stellar singers of the Great American Songbook, it featured interviews and CD reviews by numerous writers (not just me!) who were better than almost anybody writing in the popular press.

Check it out here.